Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak was published in 1963, won the Caldecott Medal, revolutionized children’s literature, and has become a library, household, and even White House staple book ever since. Nineteen million copies worldwide. You can read it in over forty languages—if you can read in multiple languages.

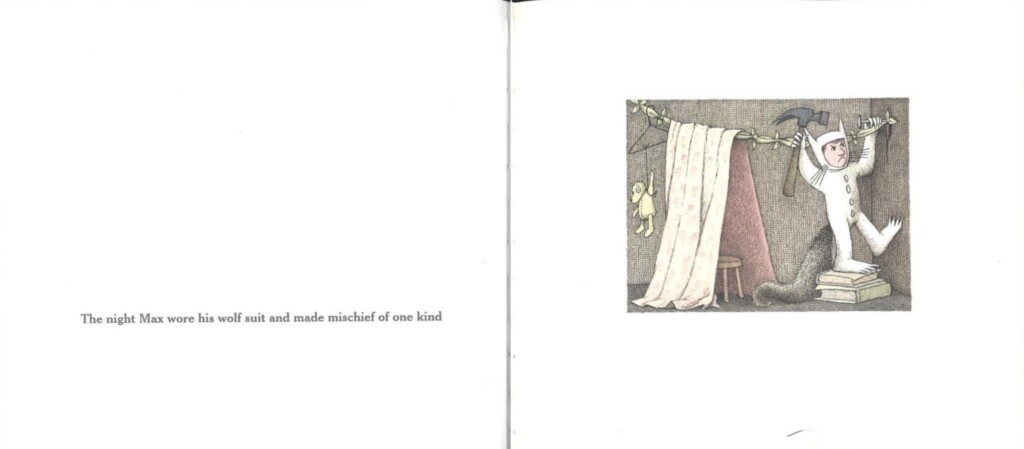

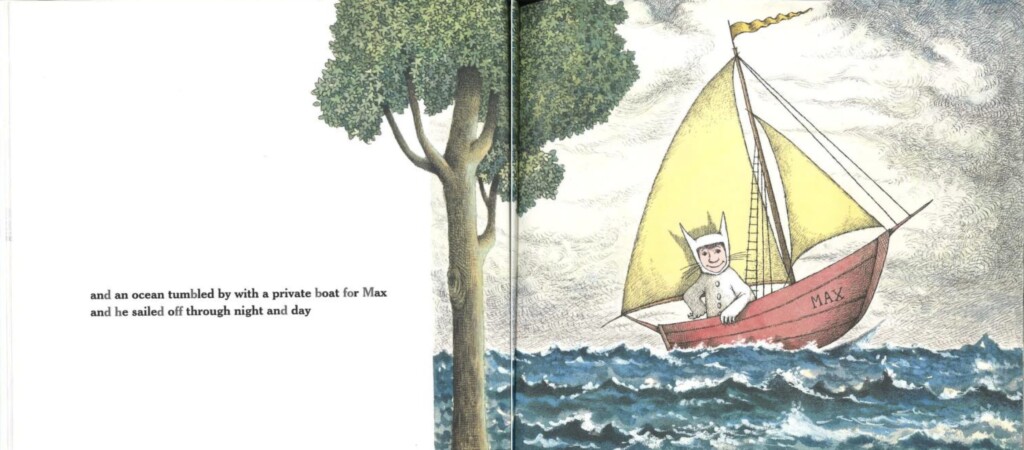

When you first meet Max on the page, he’s in the most traditional picture book format out there. Words on the left side, image on the right. Of all characters, Max would be the one to feel trapped in that rigid structure. He’s small, surrounded by suffocating white space. He’s in a box from the choices he’s made before the book ever began.

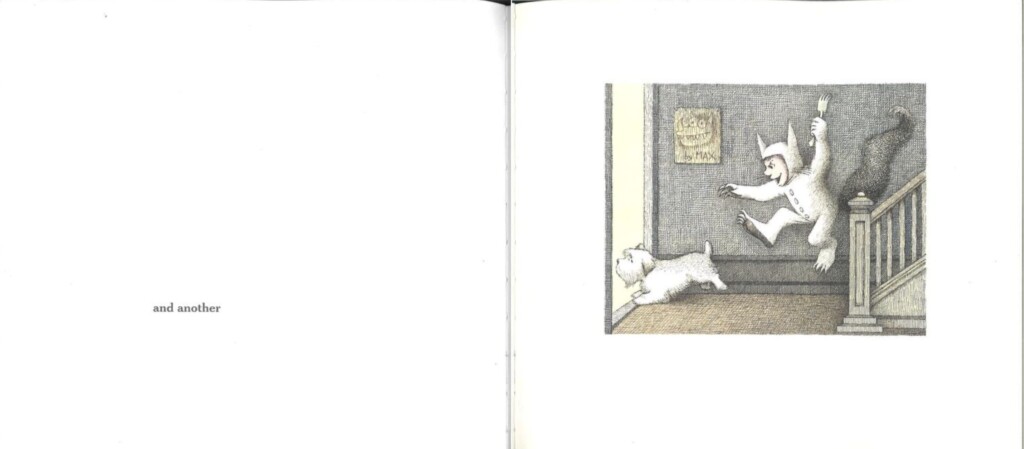

Each page I would flip, Max’s body would change directions, like he’s been in every corner of the house, causing maximum chaos. I hated how slow the dog looked compared to the leap that Max takes after him. That fork was going straight into its little hind end. That was the kind of mischief I couldn’t wrap my head around—the kind that strung up stuffed animals or sporked family pets.

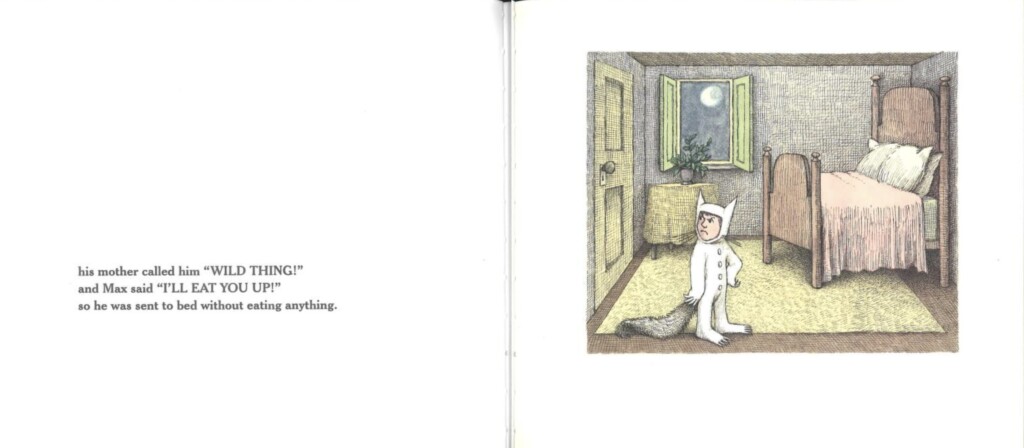

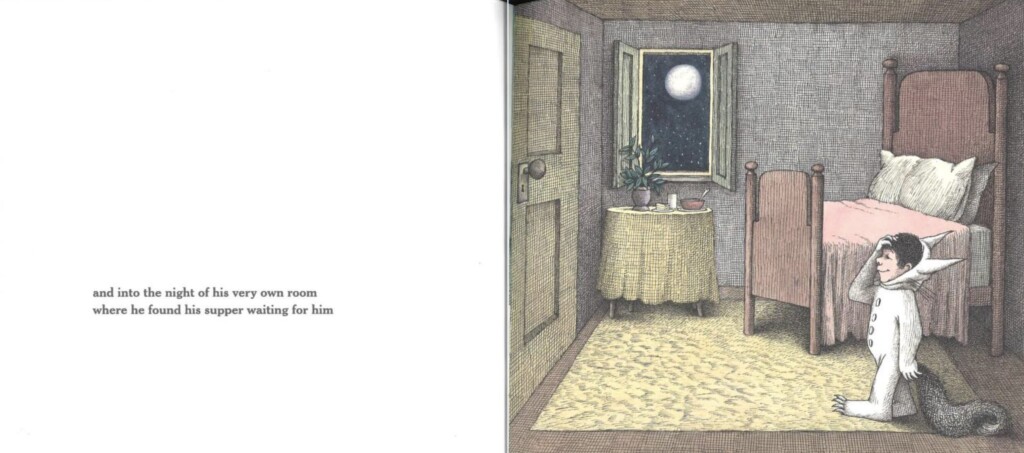

But I also couldn’t understand the bedroom that Max was sent to—supposedly his bedroom—that looks like the opposite of Max’s chaotic personality. His bedroom is stale. No toys, no drawings, nothing that makes the room feel like Max. When his mom and him get into a fight, I don’t get to see it as the reader. Sendak’s strategy is to balance when the “Words are left out—but the picture says it. Pictures are left out, but the word says it.”

When I saw that room, I knew everything about Max’s mom. The words didn’t have to tell me anything.

His mom is a vacuum-er. Probably an immaculate dust-er too. I know, because my mom has probably won Olympic medals for how good and accurate of a vacuum-er she is. Don’t get me wrong, she let me have the most messy, most dirty childhood I could have wanted, full of imaginative play and just as many chaotic moments as Max. But surrounding those memories are the careful acts of putting things away before the vacuum could suck the toy into oblivion.

I used to have recurring nightmares that my mom and the vacuum would suck my beloved baby blanket up, and we wouldn’t be able to get it back from its munching mouth. My mom assured me that it was just a nightmare, and the vacuum couldn’t do that. But it’s eaten a lot of much bigger and more structurally sound things since those nightmare days, and now I’m fairly certain the Kirby vacuum could eat whatever it puts its machine-mind to, and my mom was just saying that so I would go to sleep.

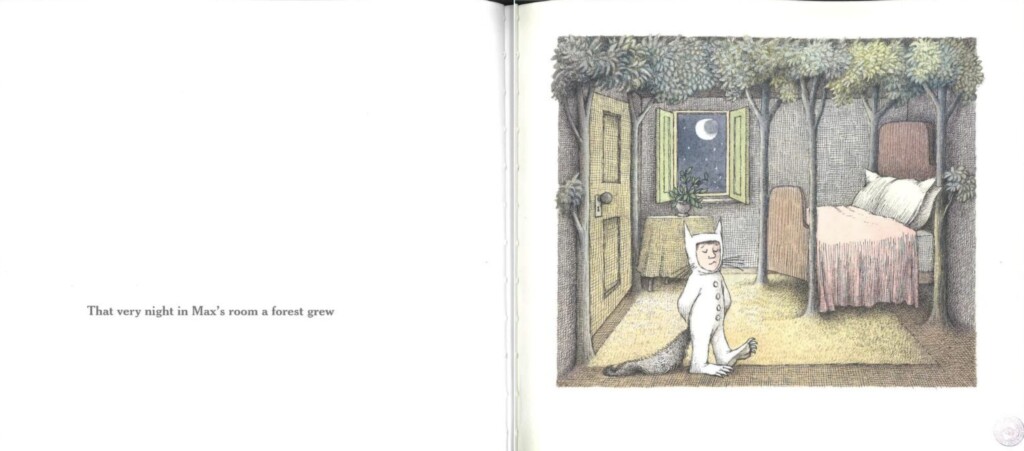

Unlike my experience, Max’s personality can’t squeeze itself through his mom’s rigid cleaning schedule. His imagination gets constrained to an ugly rug, a table, and a bedspread that he probably didn’t get to choose. His wildness—which was hammering nails into walls, scratching floors, and misplacing cutlery—goes against her order. I used to sweat, worrying what she would think when she realized Max’s floorboards had grown into trees. That would be hard to vacuum.

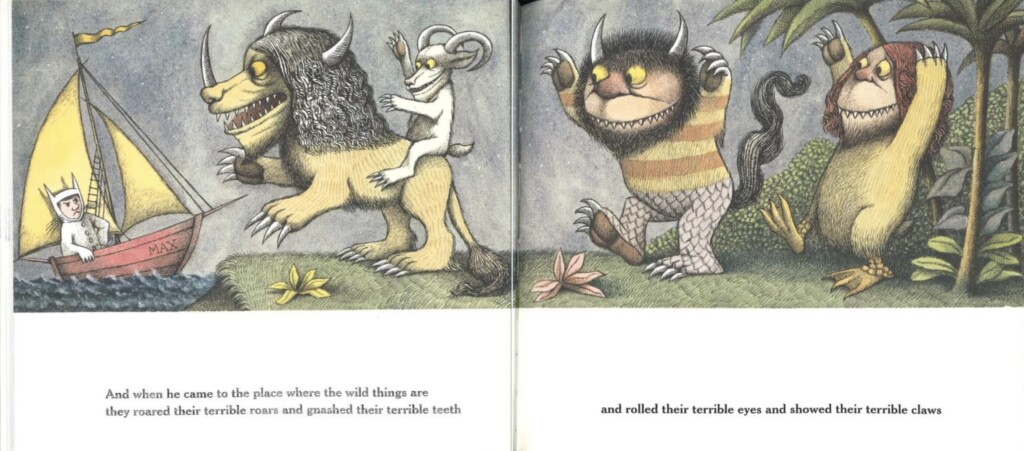

But as soon as his room starts to transform, the white space starts to disappear. The trees break the boundaries of the traditional picture book format. I couldn’t believe he was traveling in and out of weeks until he could find a place where he belonged—a space where the text is confined to little rectangles, and the wild things have control of the pages. Sometimes whole spreads.

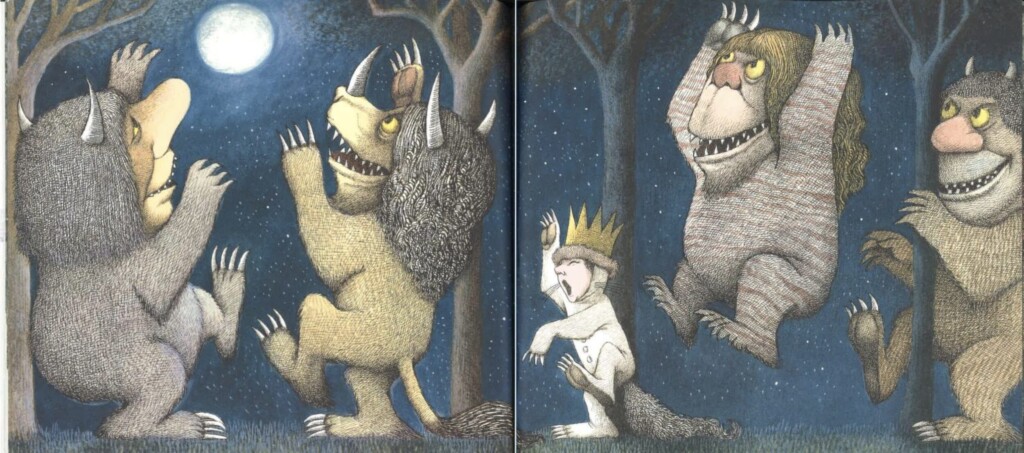

When he’s king, there’s this terrible crescendo with the rumpus.

The spreads are overtaken by the illustrations, the pigment gets heightened, and the words and white space disappears. A vacuum has never seen this realm before. No structure, no tradition, and definitely no vacuums. The silence of the words let me the reader fill in the crashing chaos of the stomping monsters. Adding words would have made the pages quieter.

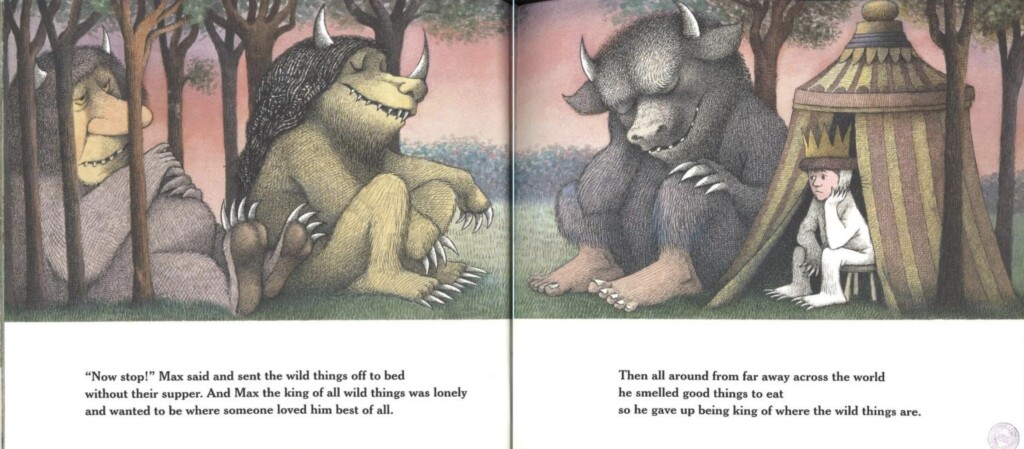

Rumpusing can only last so long, though, and the structure reappears when Max pulls the same trick that his mom did to him earlier in the story—he sends the wild things to bed without supper. With his new position as king, something’s happened. His expression is so hard to read, that as a kid I just had to buy it when the text said he got lonely.

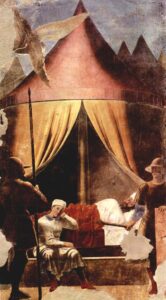

It’s an epiphany, I think. Because look at Piero della Francesca’s “Dream of Constantine” fresco in Arezzo, which has a similar composition, color scheme, and mood to the page when the rumpus ends. It depicts the vision of the Roman emperor Constantine the night before the battle against Maxentius (hum, suspicious). The angel in the upper left corner tells Constantine, lying in his tent, to fight under the sign of the cross, rather than the sign of Rome. His servant, looking bored and unaware of the angel, sits in the foreground and looks a lot like Max in his tent.

I wasn’t philosophizing about this as a kid. I’d rather not philosophize about it now, either, because I used to get so mad about people doing that to books until there wasn’t any joy left in reading it. But I think what’s happening here is Max, for the first time, sees his mom, and not her cleaning schedule.

I’ll never see Max’s mom. Sendak never depicts her, even when Max returns home. I think as a kid, it was hard to not imagine her as my mom because of that. Max doesn’t apologize, there’s no moralizing (which I especially hate in books), and there’s no sappy exchange of forgiveness. His room looks mostly the same, so I know that his mom hasn’t given in to his want of chaos, but it is bigger. The suffocating white border around his room has disappeared.

(Though it always freaked me out that the moon phase had changed, as if Max really was gone for a long time.)

Here, grace comes in the form of food waiting for him. Still hot, no matter how long he was gone.

One point for perfect mom-timing.

Of course, it’s ridiculous to say I believe that there’s a vacuum hidden behind the scenes that makes this book plot run the way that it does. But my experience tells me that maybe that is what’s going on here. Why not? Our experiences that we bring to books makes us keep coming back. It makes us better readers.

All nineteen million of us, and our vacuum-er moms too.

Gabrielle Eisma graduated Calvin with a BFA in studio art and writing in 2022. She’s from Grand Rapids, Michigan, where she now works as a writer and illustrator for books for (mostly) children and middle grade readers.

Thanks for helping me see an old classic with new eyes.