On the evening of Wednesday, October 29th, I was in my apartment in Chicago. While folding laundry to the sounds of John Mayer on my turntable, I dozed off among the piles of socks and sweatpants and t-shirts on my bed. I woke up around 3 a.m. in what were now the early hours of Thursday, October 30th. I went quietly to the living room, lifted the clicking needle off the record, and grabbed my phone from the couch where I had left it. As the screen lit up, I saw I had a missed call and a voicemail from my dad, left at 1:50am. This call and voicemail could only mean one thing.

For a year, I’ve kept my phone with me at all times (and even started sleeping with it under my pillow) so that I wouldn’t miss this call. But there I was, standing in my robe in my living room in the middle of the night like an idiot—and I had missed it. Without even bothering to play the voicemail, I ran to grab a duffle, my toiletry bag, threw on some clothes and my coat, and was already merging on the highway heading east towards Michigan within ten minutes.

Chicago streets and highways are never pitch-black, even at three in the morning. The city has an iconic orange glow that comes from the street lamps. But as I sped over the enormous skyway (which was the fastest way out of the city), my surroundings got darker and darker. As I came up over the bridge, I couldn’t even distinguish the black of the lake from the black of the sky. The roads were quiet. The only sound was my own engine revving at one hundred miles an hour down streets that were devoid of any other sign of life. One single thought in my head played over and over and over, like the clicking sound of the needle at the end of my record at home: “I missed the call. I missed the call.”

I was in Grand Rapids by 7 a.m. My dad had gone into surgery about an hour earlier. The dawn had barely cracked. Nurses and clinicians who had been working with my dad for months came from their respective wings across the hospital to check on my mom. They brought her a blanket, tissues, and even a Starbucks gift card. They knew it would be a long, long day. Uncles, aunts, more family, and close friends gradually filtered in. As the sun moved in the sky, our clan took over an entire corner of the waiting room—and suddenly it was almost dinner time but of course none of us had thought about eating. Twelve hours later, a kind nurse ushered us all into a private room in the back where families are brought to get their news. We clustered on a couch and pulled in extra chairs from outside. My dad’s surgeon finally came in, shut the door behind him, and gave us the long awaited update.

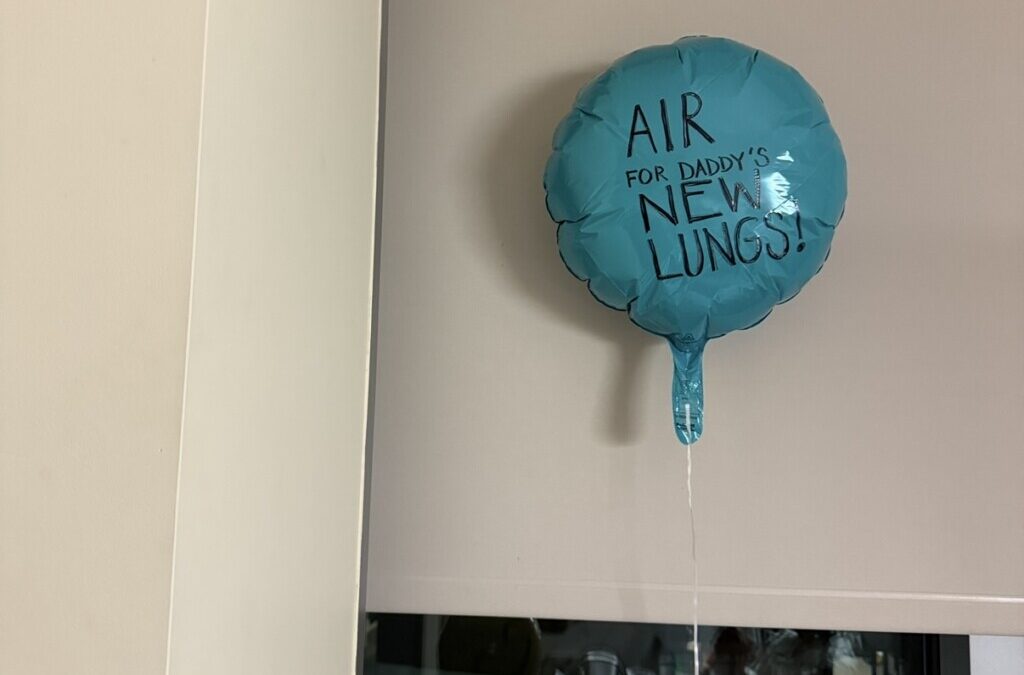

My dad had two new lungs.

My mom and aunts started weeping, thanking the doctor for his kindness, his skill, and for the dedication of his hands to God’s work. Then my mom got on her knees and thanked God for bringing my dad through the surgery. The rest of the family joined her in prayer, tears, and gratitude. We were instructed to go up to the seventh floor, where he’d be transferred from the operating room into the ICU, and we’d be able to see him briefly.

My dad woke up from his anesthesia early Friday morning. My mom and I sat in the waiting room eating our Chick-fil-a takeout at lunchtime, and discussed what protocols we would have to implement at the family store now that my dad wouldn’t be able to work for several months. We chatted, ate, and brainstormed about this next phase of life, about my dad’s recovery—when suddenly behind us, we heard a young woman inhale a sob, which turned into weeping. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see a middle-aged man with his arms wrapped around her as her body shook. My mom and I made eye contact and both lowered our chicken sandwiches, suddenly losing our appetite, as we were sobered into remembering that—within just the last several hours—we were made the lucky ones. In the hours that we waited just the day before, we had no clue if we would be making plans for recovery, or for a very painful alternative.

Hearing the cry of that young woman also caused me to think for the first time of the individual whose lungs were now inside my father’s chest, giving him new breath, extending the length and quality of his life, as well as the ability for him to remain in his loved ones’. It made me realize that there was a family out there somewhere who was grieving a loss at the very same time that my family received the most precious gain. That thought didn’t extinguish my immense gratitude, but it tainted it.

Over the last two years, we didn’t know which day would happen first: if my dad would get new lungs, or if the disease would progress and take him to the end. Being in this unknown for such an extended period of time, your body is kinda forced to attempt to impossibly prepare for both scenarios. On the one hand, you remain hopeful; you talk about healing, and make plans for “when he’s better.” On the other hand, you wrestle and cope with the reality that he is actively dying and will continue on this spiral unless there’s a miracle. It’s like you have to preemptively grieve their loss to a certain degree before they’re actually gone. There are two hour glasses, two realities, that are spitting out sand at different rates in your head and you never, at any point, have a grasp of which one is ahead.

That is, until you get the call.

My mom told me later that, on the way to the hospital, my dad was quite calm. She asked him if he was nervous or scared, and he just simply wasn’t. In fact, she said he was even excited. He wanted new lungs. He was ready for new lungs. The pain that he had been experiencing and managing for so long was so exhausting, he was just ready for whatever came next; whether it went well or not, I don’t know if he even cared anymore—he was just ready to finally be over with the spiral.

And now, he’s recovering at home. We can wind up the miles and miles of plastic oxygen tubing that have twisted around the rooms of our house and toss them out. We can send the buzzing and beeping giant oxygen machines back to the clinic from whence they came. The gift of someone else’s death meant that my dad could start to breathe on his own again; he could laugh without the fear of coughing or choking, he could walk inside from the car on his own, and we could all finally stop wondering which hourglass was going to run out first. God knows how many more years he was just gifted with these new lungs. It’s a complicated thing to consider grief in light of one’s gratitude—though the two seem to often be forced to exist simultaneously.

Sophia (‘19) double-majored in theatre and religion and insists that her life is a “storybook.” She lives in an apartment above a flower shop in downtown Chicago and has multiple roles working across the arts in comedy, music, theatre, film, and visual art—though her greatest passion is writing. Her work includes stage plays, screenplays, and articles, focusing mostly on cultural trends, comedy, reviews, and religious satire. She loves road trips, visiting her family in Grand Rapids, hunting for the perfect latte, and rescuing plants from the flower shop’s dumpster.

The family members of the organ donor probably feel a sense of grief and gratitude too. That persons life gets to carry on in all of the people who they helped. They wanted to be able to do something meaningful even after they had passed. I’m so grateful that your dad is doing well! Thanks for sharing in such a beautiful way!

Oh wow! That sounds so scary. So glad to hear that your dad has a new chance!