Our theme for the month of October is “states.”

Colorado has trolls.

They hide off the beaten paths in the mountains, outside of major population centers. Strangely anachronistic, they are both new and ancient. Both local and alien.

Colorado doesn’t have much mythos. The place this was before it was Colorado, land inhabited by several nations, has generations of myth and folklore. But Colorado, the “Centennial State,” starts squarely in the modern era in 1876.

Despite the fact that they are apparently 100,000 years old, even the lore of the trolls has a contemporary flavor. One article about sites affiliated with local folklore suggests the trolls came for the ski season and stayed.

People in Colorado make a bizarrely big deal about being “a native.” Perhaps because the population around here is fairly mutable: medical professionals on travel contracts, military personnel, Texan and Californian transplants, and skiers who just stayed.

But people’s connections to a place, their personal folklore, can surprise you.

I remember thinking it was an odd, poetic, potentially significant twist of fate when my Portland-born ex-boyfriend told me that his grandfather had, as a young man, stolen a train in Leadville, an isolated mining town with a blunt, literal name ten thousand miles above sea level in the Rocky Mountains. Mind you, this mythic grandfather had not robbed a train, he’d stolen the whole train for a joyride, if I remember correctly.

My own grandfather, a bit of a renegade himself, had been hauled off to Leadville from rural Virginia in the hopes that running a pool hall with my great-grandfather would curb my grandpa’s mischievous ways. (My grandpa’s exploits included vandalizing his one-room schoolhouse.) As it turned out, the task of reforming my grandfather was too much for my great-grandfather and required the whole US Navy.

I thought perhaps it mattered that this ex-boyfriend and I had stories that intersected in Leadville with troublemaking grandfathers. Despite being born and raised in different states, we’d come from the same sort of idiot? Scoundrel? Anti-establishment free-spirit? It depends on how you tell the story.

I have always considered myself the family historian. As a little girl, I would sit with my mom on the puffy comforter of her enormous bed, and beg her to show me the Family History Book.

Bound in worn red velvet with a brass bee in one corner of the cover, the Family History Book was compiled by one of my great-grandmothers. It chronicles the births, marriages, voyages, and deaths of my ancestors as far back as the Romans in Gaul and Britannia. Charlemagne is in there, and a handful of French knights and Welsh lords, some of the American founding fathers named Adams—again, good, or bad, or both depending on how you tell the story. My favorite part of the Family History Book has always been the bright, handpainted coats of arms with their dragons, lions, and fleur-de-lis. I love having a story that transcends locality or nationality and brushes fairytales and myth.

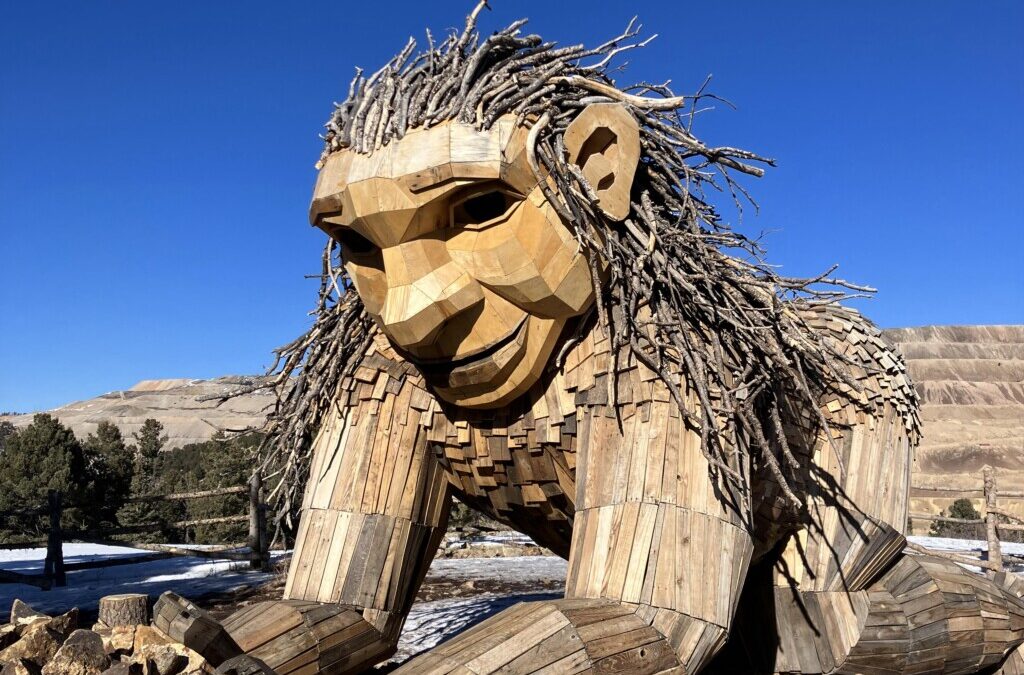

Rita, the troll I have personally had the privilege of visiting with, also has a story that straddles time and place. She is a colossal sculpture created by Danish artist, Thomas Dambo, mostly of used furniture from Denmark, making her both old and new, both a local and an immigrant with origins here and elsewhere.

Colorado has two of more than 100 that Dambo has created worldwide. Dambo pulled his trolls from Danish folklore and crafted his own history for his creations.

According to an article on Rocky Mountain PBS’s website, Dambo explained, “[The trolls] become a link between the natural world and the humans.”

Dambo says his gentle giants fear humans but also hope to help us live in better harmony with our world. This message is poignant in the context of the dusty gravel, strip-mined slopes which serve as a backdrop for Rita.

Rita was completed in 2018, and, therefore, her story intersects with a lesser known, uglier piece of Colorado lore.

Like many western states, Colorado has a complicated racial history. Many African Americans built successful lives in Colorado, including William Jefferson Hardin, Wyoming’s first black state legislator, who later in life served as mayor of Leadville, of all places. But records also show enslaved people being brought to Colorado until slavery was officially outlawed in the state in 1877, with the exception of labor imposed upon convicted criminals, an exception later abolished, surprisingly recently, in 2018.

I love history for the connections. And most folklore is also about connections. While folklore does feature overwhelmingly powerful natural forces and perplexing phenomena, many stories also showcase human power to influence events around us through courage or cunning or kindness. Even if we can’t see or understand the big picture, the stories sometimes tell us, our actions have consequences. But most folklore tales aren’t fables. The lessons we learn and the connections we draw are mostly up to us. It’s all in how you tell the story.

We make meaning out of the connections we draw. Sharing the particular history of having wayward grandfathers engaged in highjinx in Leadville proved more coincidence than connection for me and my ex-boyfriend. And Rita has nothing to do with the abolishment of slavery in Colorado except that they were coincidentally completed in the same year.

But 2018 is not that long ago. And the fact that the scale-like shingles that clothe Rita are still honey-gold and not grey with age and fading into the mining debris behind her, is maybe a good reminder that what we call “history” is not that far from us.

Once, while I was giving a tour of a local historical house, an elderly tourist pulled me aside and informed me in a somewhat indignant tone and a heavy Russian accent that the house we were in was “brand new” compared to the 500-year-old house he was born in. What makes something old, historic, or significant? How long does it take to become a local? It’s all in how we tell the story.

We shouldn’t rush to turn history into myth in order to gain a comfortable distance from it or to draw too firm a dividing line between our stories and the lore of a trouble-making grandfather.

But I do not say that to invoke some guilt harpy or specter of inherited sin to pursue us like in a Greek tragedy. We are not our family nor our folklore. It is a tool to help us, something which we can learn from or recycle and draw new meaning from as we make new stories, new art—like Rita.

Emily Stroble is a writer of bits and pieces and is distractedly pursuing lots of novel ideas and nonfiction projects as inspiration strikes. As an editorial assistant at Zondervan, she helps put the pieces of children’s books and Bibles together. A lover of the ridiculous, inexplicable, and wondrous as well as stories of all kinds, Emily enjoys getting lost in museums, movies old and new, making art, the mountains of Colorado, and the unsalted oceans near Grand Rapids. Her movie reviews also appear in the Mixed Media section of The Banner and her strange little stories of the fantastic are on the Calvin alumni fiction blog Presticogitation. Her big dream is to dig her hands deep into the soil of making children’s books as an editor…and to finally finish her children’s novel.